Manual Touch and the Autonomic Nervous System: Mechanisms & Clinical Applications for Manual Therapists

Nov 09, 2025

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is important for all manual therapists to understand. When we treat biomechanical dysfunction we have to consider how therapeutic touch can influence a clients systemic physiology, not just the local structures. The ANS is the unconscious regulator of bodily functions — including heart rate, digestion, respiration, vascular tone, and endocrine activity — and is interwoven with how patients experience pain, tension, and stress. Treatments that include ANS regulation can have cascading effects on our clients global health, recovery, and symptom regulation.

This blog explores the mechanisms through which touch and manual therapy can influence the ANS, highlighting both the peripheral and central pathways involved. It also considers clinical implications, guiding you to be aware of ANS involvement in your clients' presentation, and in the effect your treatment has over the clients global health and regulatory processes.

The Autonomic Nervous System: A Quick Refresher

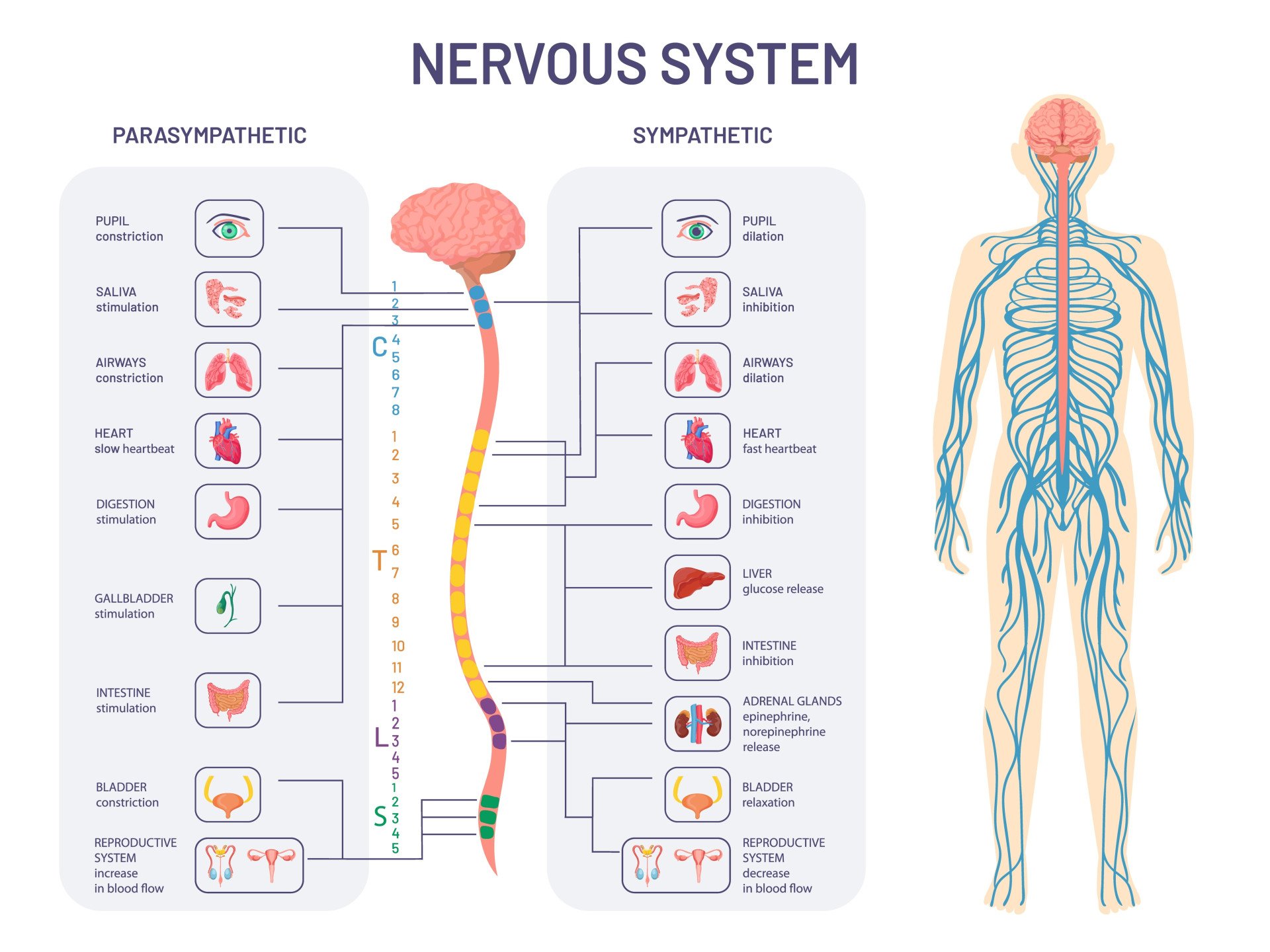

The ANS is the unconscious regulatory system of the body. It controls heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, respiration, pupillary reactivity, sweating, urination, sexual function, and viscera regulation, maintaining cellular, tissue, and organ homeostasis while protecting against internal and external stressors (Aydin et al., 2021). We can divide it into three branches:

- Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS): Catabolic and energy-expending, activating the fight-or-flight response. Presynaptic neuron bodies are in the gray matter of the thoracic and upper lumbar spinal cord levels (T1–L2/3), while postsynaptic neuron bodies are located in paravertebral and prevertebral ganglia. The SNS mobilizes energy, modulates vascular tone, and releases norepinephrine and epinephrine systemically via the adrenal medulla (Gibbins, 2014).

- Parasympathetic Nervous System (PSNS): Anabolic and restorative, promoting digestion, repair, and energy conservation. Presynaptic neuron bodies are located in cranial nuclei (III, VII, IX, X) and sacral segments (S2–S4). Postsynaptic neurons are often embedded within or near target organs, allowing precise modulation. Acetylcholine is the primary neurotransmitter (Kandel et al., 2021).

- Enteric Nervous System (ENS): Governs gastrointestinal activity and interacts with both sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions to regulate digestion.

The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) provides parasympathetic innervation to thoracic and abdominal viscera, influencing heart rate, digestion, and is as a key structure for sensory input from the viscera to the central nervous system (Breit et al., 2018). Its accessibility in the cervical and thoracoabdominal regions makes it particularly relevant for manual therapy interventions.

Clinically, ANS regulation is relevant in chronic pain, dysautonomia, tension disorders, and stress-related conditions. Objective markers include heart-rate variability (HRV), skin conductance, cortisol levels, and baroreceptor sensitivity (Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017).

(Guy-Evans, 2005)

Mechanisms by Which Touch and Manual Therapy Influence the ANS

Cutaneous and Fascial Mechanoreceptors

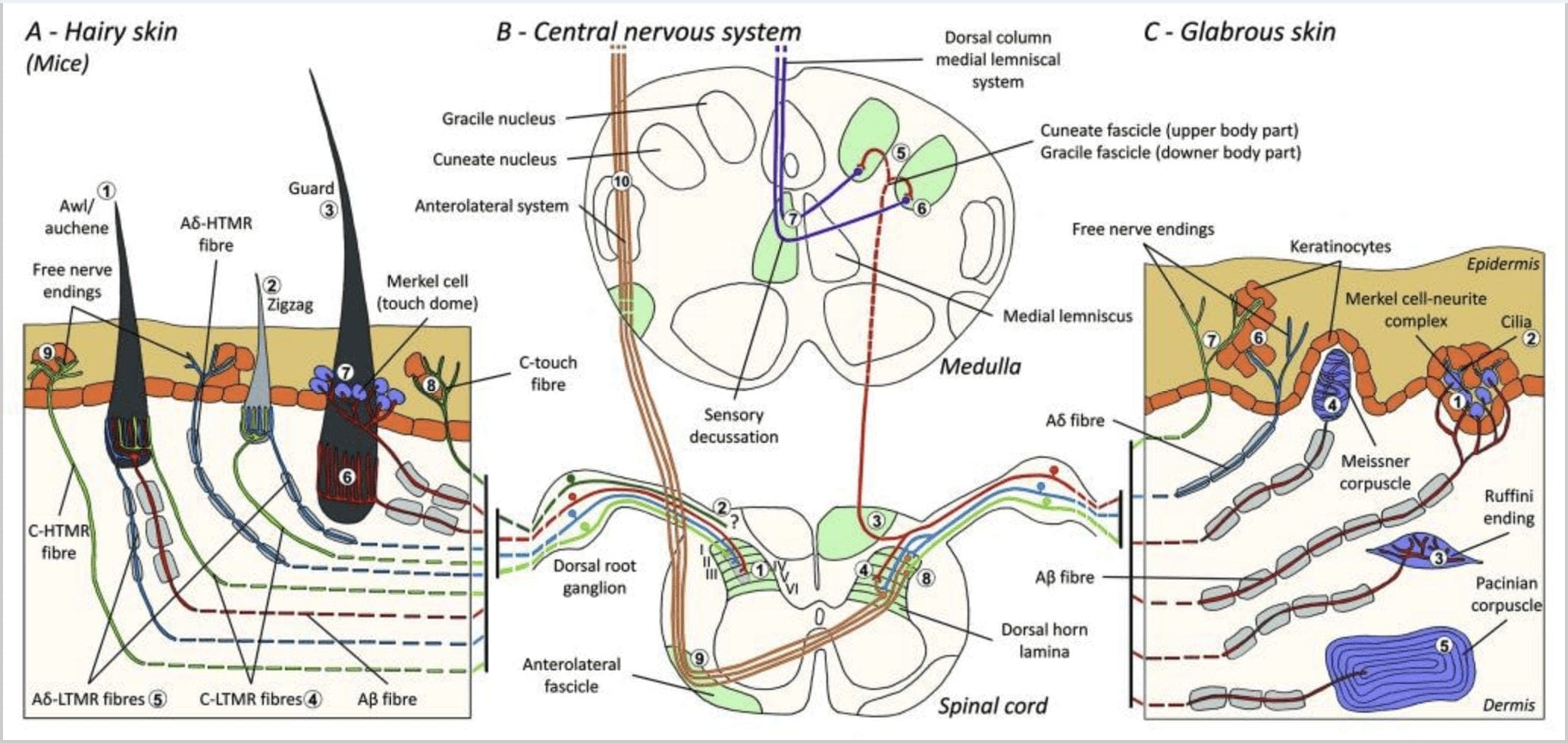

There are many mechanoreceptors in the skin and fascia that respond to stretch, pressure, vibration, and shear forces. These receptors have Aβ afferents fibers, which carry fast, large-diameter signals to the central nervous system, and C-tactile fibers, which respond to gentle, affective touch (Walker & McGlone, 2013).

Fascia is more than just connective tissue; it is highly innervated and may contain some smooth muscle, allowing dynamic modulation of tone in response to manual input (Schleip et al., 2012). Activation of mechanoreceptors in the fascia generates afferent signals that project to the spinal cord and supraspinal centres, potentially influencing reflexive muscle tone, interstitial fluid dynamics, and even higher-order body perception.

Fascial receptor stimulation has been proposed to:

- Reduce sympathetic activity via spinal and supraspinal interneurons (Schleip et al., 2012)

- Lower muscle tone through reflexive inhibition of alpha-motor neurons (Findley et al., 2012)

- Influence fluid dynamics and interstitial pressure (Schleip et al., 2012)

- Alter body perception and proprioception

By targeting fascia and superficial tissues, therapists may influence local tissue tone while also affect the systemic autonomic tone and balance.

(Roudaut, Lonigro, Coste, Hao, Delmas, & Crest, 2012)

Modulation of Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Output

Manual therapy may influence sympathetic-parasympathetic balance. Gentle, rhythmical touch, slow massage, or craniosacral techniques can increase parasympathetic activity and reduce sympathetic drive, as evidenced by HRV improvements and decreased cortisol or norepinephrine levels (Field et al., 2005).

In interventions targeting the cervical and thoracoabdominal regions, the vagus nerve is very important in the reduction of sympathetic drive. Vagal afferents detect stretch and pressure changes, the sensory input is sent to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the medulla and may inhibit sympathetic centers while promoting parasympathetic outflow, improving digestion, reducing heart rate, and modulating inflammatory responses (Breit et al., 2018).

Manual therapy techniques, craniosacral therapy, and visceral manipulation may also influence the vagal tone, either directly through cervical or thoracoabdominal stimulation or indirectly via fascial mechanoreceptor activation (Henley et al., 2024).

Central Integrative and Descending Modulatory Systems

Touch-induced afferent input is processed centrally. The spinal cord, brainstem, and forebrain receive the mechanoreceptive signals, and coordinate autonomic and behavioral responses. The periaqueductal gray (PAG), parabrachial nucleus (PBN), hypothalamus, and limbic regions are central hubs, modulating sympathetic and parasympathetic activity in response to sensory, emotional, and contextual cues (Thayer & Lane, 2009).

These central circuits may be engaged by manual therapy. Craniosacral, affective touch, rhythmic palpation, or fascial/membranous/ligamentous balance techniques can create a sense of safety, leading to increased parasympathetic tone via vagal pathways (Walker & McGlone, 2013). This central modulation can be measured through reduced heart rate, slowed breathing, and decreased muscle tension.

(Riganello, Vatrano, Cortese, et al., 2024)

Structural, Vascular, and Fluid Influences

Tissue biodynamics, vascular tone, and fluid distribution are all influenced by manual therapy. Changes in interstitial pressure or tissue viscosity affect baroreceptors and mechanosensitive signaling, which feed-back to the central autonomic centers (Schleip et al., 2012). Changes in respiratory mechanics and thoracoabdominal rhythm also influence vagal tone and cardiac function, further highlighting the interconnectedness of mechanical and autonomic processes.

Context, Expectation, and Therapeutic Environment

The environment in which manual therapy occurs is also important. A sense of safety, trust, softness, and client collaboration, can enhance parasympathetic tone. While stress, discomfort and tension can amplify sympathetic tone. The effects of Manual therapy are therefore, the result of both the hands-on input and the broader environmental context (Safran & Kaya, 2025).

Clinical Implications for Manual Therapists

Assessment

Manual therapists should assess for signs of ANS dysregulation, including:

- Resting tachycardia or bradycardia

- Low HRV

- Altered breathing patterns

- Skin temperature asymmetries

- Muscle tension or rigidity

These assessments can help determine whether interventions targeting ANS regulation are warranted.

Treatment Planning

Techniques may be chosen with ANS modulation in mind:

- Gentle input: Likely to improve parasympathetic activation; perfect for clients with sympathetic dominance or heightened stress response. Craniosacral, affective touch, rhythmic palpation, or fascial/membranous/ligamentous balance techniques

- Target regions: Cervical, occipital, thoracoabdominal regions, and the vagus nerve may increase parasympathetic output.

- Integrate with breath: Combine manual therapy with diaphragmatic breathing or guided relaxation will enhance vagal tone.

Clients with chronic pain, fibromyalgia, POTS, migraines, or high stress may particularly benefit from strategies that support parasympathetic activation.

Monitoring Outcome

Beyond musculoskeletal outcomes, consider monitoring:

- HRV changes

- Resting heart rate

- Breathing pattern

- Subjective sense of calm or relaxation

This allows therapists to capture both objective and subjective markers of autonomic regulation.

Practical Framework for Implementation

- Screen for autonomic dysregulation: Evaluate resting HR, HRV, breathing patterns, and sympathetic signs.

- Set goals: Include autonomic regulation alongside structural objectives.

- Choose techniques: Consider gentle fascial work, cranial or visceral techniques, and mobilizations over vagal-rich regions.

- Integrate breathing and relaxation: Encourage diaphragmatic breathing and guided relaxation to enhance parasympathetic activation.

- Monitor outcomes: Track subjective calm, objective HR/HRV, and clinical signs (tension reduction, posture, recovery).

Contraindications and Caveats

While evidence supports the potential for manual therapy to modulate the ANS, results are variable and context-dependent (Posadzki et al., 2021). The ANS is highly complex, and touch-based interventions are one of many factors influencing autonomic balance. As manual therapists, we should combine clinical observation, patient feedback, and, where possible, objective measures to guide interventions.

Conclusion

While manual therapy does not guarantee ANS modulation, the evidence supports the potential for touch to influence autonomic balance. Vagal activation, reflexive modulation via spinal and supraspinal interneurons, and fascial mechanoreceptor stimulation all contribute to this complex interplay. By integrating ANS awareness into assessment, technique selection, and patient monitoring, manual therapists can enhance the physiological and therapeutic benefits of their practice.

References

- Aydin, M., et al. (2021). The autonomic nervous system and homeostasis. Archives of Gastroenterology, 28(3), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.14744/agri.2021.43078

- Breit, S., Kupferberg, A., Rogler, G., & Hasler, G. (2018). Vagus nerve as modulator of the brain–gut axis in psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 44. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044

- Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Cortisol decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. Int J Neurosci. 2005 Oct;115(10):1397-413. doi: 10.1080/00207450590956459. PMID: 16162447.

- Findley, T., Schleip, R., & Chaitow, L. (2012). Fascia research II. Elsevier.

- Gibbins, I. (2014). Autonomic nervous system: Organization and function. In Fundamental Neuroscience.

- Guy‑Evans, O. (2025, May 1). Autonomic nervous system (ANS): What it is and how it works [Image: Nervous system]. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/autonomic-nervous-system.html

- Henley, C., et al. (2024). Effect of manual osteopathic techniques on the autonomic nervous system: A systematic review. Frontiers in Medicine, 11, 1358529. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1358529

- Kandel, E., Schwartz, J., Jessell, T., et al. (2021). Principles of Neural Science (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Posadzki, P., Ernst, E., & Lee, M. (2021). Do manual therapies have a specific autonomic effect? An overview of systematic reviews. PMC, 8638932. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8638932/

- Riganello, F., Vatrano, M., Cortese, M.D. et al. Central autonomic network and early prognosis in patients with disorders of consciousness. Sci Rep 14, 1610 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51457-1

- Roudaut, Y., Lonigro, A., Coste, B., Hao, J., Delmas, P., & Crest, M. (2012). Touch sense: Functional organization and molecular determinants of mechanosensitive receptors. Channels, 6(4), 234–245. https://doi.org/10.4161/chan.22213

- Safran, E. & Kaya, Y. (2025). Contextual and placebo effects of suboccipital myofascial release: evaluating its influence on pain threshold, cervical range of motion, and proprioception. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 26(1), Article 502. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-025-08741-6

- Schleip, R., Findley, T., Chaitow, L., & Huijing, P. (2012). Fascia: The tensional network of the human body. Elsevier.

- Shaffer, F., & Ginsberg, J. (2017). An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 258. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00258

- Thayer, J. F., & Lane, R. D. (2009). Claude Bernard and the heart–brain connection: Further elaboration of a model of neurovisceral integration. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 33(2), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.004

- Walker, S. C., & McGlone, F. P. (2013). The social brain: Neurobiological basis of affiliative behaviours and psychological well-being. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(9 Pt 2), 2007–2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.05.017